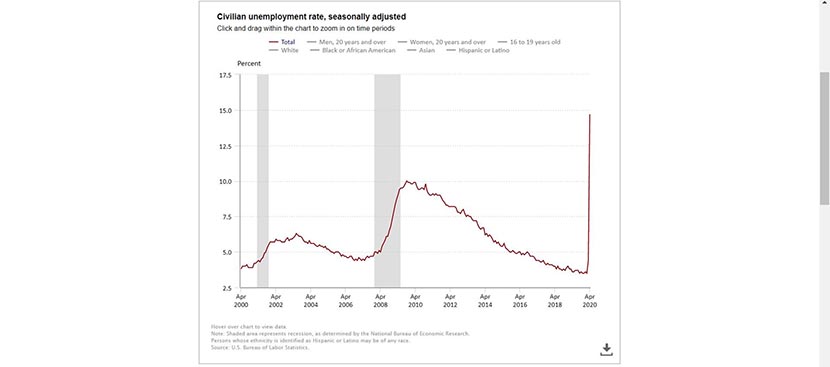

Labor Dept. Reports 20.5 Million April Job Losses; Unemployment Rate Jumps to 14.7%

One of the worst weeks in U.S. economic history ended Friday with the Bureau of Labor Statistics reporting a staggering 20.5 million jobs lost in April and the unemployment rate jumping to its highest level since the Great Depression.

BLS reported total nonfarm payroll employment fell by 20.5 million in April, wiping out nearly a decade of job gains. The unemployment rate spiked by more than 10 percentage points to 14.7 percent—the biggest one-month increase in the report’s history, dating back to 1948—as the effects of the coronavirus pandemic slammed the U.S. economy with full force.

The report said employment fell sharply in all major industry sectors, with particularly heavy job losses in leisure and hospitality. The number of unemployed persons rose by 15.9 million to 23.1 million in April. BLS also revised down numbers for February and March.

Additionally, BLS reported the labor force participation rate decreased by 2.5 percentage points over the month to 60.2 percent, the lowest rate since January 1973. Total employment, as measured by the household survey, fell by 22.4 million to 133.4 million. The employment-population ratio, at 51.3 percent, dropped by 8.7 percentage points over the month, the lowest rate and largest over-the-month decline in the history of the suvey.

“The extraordinary impact from COVID-19 social distancing measures and business closings is weighing on the job market in unprecedented ways,” said Joel Kan, MBA Associate Vice President of Economic and Industry Forecasting. “April was the first full month of the impact and resulted in a record-loss of 20.5 million jobs. Essentially all sectors lost jobs over the month. Leisure and hospitality, the sector perhaps most impacted by closings and restricted operations, saw a 7.6 million job decrease; retail trade suffered 2 million in job losses. The construction sector lost 975,000 jobs – close to the 2009 annual total – which is a blow to the housing recovery and might impact future housing supply.

Kan noted one hint of optimism is that 18.1 million of the 23 million unemployed were classified as “temporary” layoffs, indicating these workers expect to return to work. “Overall, the numbers were still bad,” he said. “The early impact of this deterioration on the mortgage market has already been felt by rapidly increasing rates of loans in forbearance. We expect that a rising share of loans will continue to be put into forbearance, putting further liquidity stresses on mortgage servicers.”

Kan said the housing market is in “unchartered waters” right now, “but one positive trend is that purchase mortgage applications have increased for three straight weeks, with prospective buyers gradually returning in the various parts of the country that are reopening.”

Jay Bryson, Acting Chief Economist with Wells Fargo Securities, Charlotte, N.C., warned more declines were in the offing. “Expect another horrendous labor market report in May,” he said. “As tragic as this number is, it comes as little surprise as more than 26 million individuals had filed for unemployment benefits between the March employment survey and the April survey. Sadly, there will be more job losses reported when the May report is published next month, because seven million additional individuals have subsequently filed for unemployment benefits.”

Odeta Kushi, Deputy Chief Economist with First American Financial Corp., Santa Ana, Calif., said the housing industry was particularly hard hit with an 11 percent yearly decline in residential construction workers.”

“The loss in residential construction jobs negatively impacts the pace of home building because building a home does not readily lend itself to outsourcing and automation,” Kushi said. “The housing market needs new supply at every point of the income spectrum, and it’s very hard to build more homes without increasing residential construction employment and productivity.”

BLS said in April, average hourly earnings for all employees on private nonfarm payrolls increased by $1.34 to $30.01. Average hourly earnings of private-sector production and nonsupervisory employees increased by $1.04 to $25.12 in April. BLS said the increases in average hourly earnings largely reflect the substantial job loss among lower-paid workers; this change, along with earnings increases, put upward pressure on the average hourly earnings estimates.

The report said the average workweek for all employees on private nonfarm payrolls increased by 0.1 hour to 34.2 hours in April. In manufacturing, the workweek declined by 2.1 hours to 38.3 hours, and overtime declined by 0.9 hour to 2.1 hours. The average workweek for production and nonsupervisory employees on private nonfarm payrolls increased by 0.1 hour to 33.5 hours.

“Interestingly, average hourly earnings, which have been rising 0.2% to 0.3% on average for the past few years, jumped 4.7% in April. But this is hardly a sign of strength,” Bryson said. “Because job losses in April fell disproportionally among low-wage workers, the average wage jumped. If, as we expect, the unemployment rate remains elevated in coming months, then growth in hourly earnings should weaken considerably.”