Faith Schwartz and Stuart Quinn From Housing Finance Strategies: Delivering Support Through Homeowners Assistance Fund

Faith Schwartz is Founder and Stuart Quinn is Managing Director of Housing Finance Strategies, Washington, D.C. Schwartz is a housing finance expert who has played a firsthand role in shaping industry best practices and public policy during her 30-year career. As founding principal of Housing Finance Strategies, she serves marquis public and private housing finance and fintech organizations with timely industry analysis and ad-hoc consulting.

Previously, Schwartz was SVP of government at CoreLogic, where she established the property data and analytics firm’s government vertical and created a public affairs office that co-hosted numerous events in partnership with the Urban Institute. She also spent five years at Freddie Mac, where she created and led an anti-predatory lending task force. In 2007 she was recruited to lead HOPE NOW, an alliance formed by the Housing Policy Council and the Treasury Department. As HOPE NOW’s executive director, she assembled a coalition of government agencies, lending institutions, nonprofits and trade associations to address challenges of the housing market crisis.

Stuart Quinn serves as Managing Director of Housing Finance Strategies. He has worked in housing finance, mortgage policy and technology in the private sector for over 10 years. Quinn joined Housing Finance Strategies in mid-2022 from Accenture to provide expertise on the landscape of fintech, mortgage modernization and housing policy.

While with Accenture, Quinn served as a Product Manager focusing on platform integrations, GSE technology integrations, end-user experience and Loan Origination Systems. Prior to Accenture, he worked in Advisory Services as Policy Research and Strategy Analyst for CoreLogic.

The Establishment of the Homeownership Assistance Fund

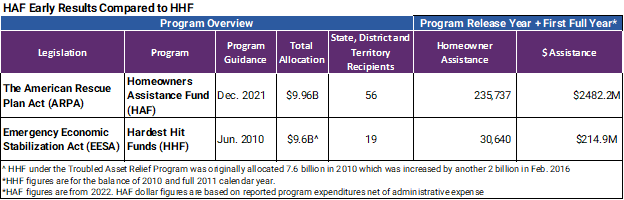

The American Rescue Plan Act passed into law in March 2021 established the Homeowners Assistance Fund that is administered by the U.S. Treasury Department and earmarked $9.9 billion in funds available for states and territories for purposes of establishing programs to assist homeowners in distress.

The structure and timing of state program rollouts varied over the ensuing year based on the coordination and implementation required for each unique program. Early on, there was some skepticism raised about the operational complexities and effectiveness of releasing 50 plus individual state programs. Now, nearly three years from the legislation’s initial passage, it is important to take stock of the status of the different programs and where dollars were effectively leveraged for purposes of addressing hardship during the pandemic and as the economy continued to recover.

Program Design and Applying Lessons Learned from the Past

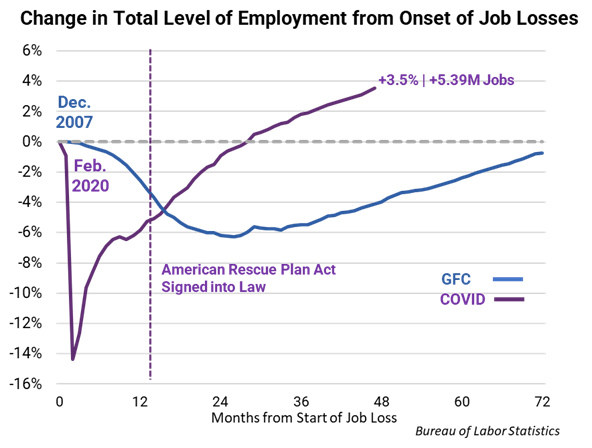

One of the primary intents of ARPA was to address the foreclosure moratoriums slated to expire after July 2021, but at the time there were also debates around the expected type or shape of the overall economic recovery, whether it would be a V-shaped or a U-shaped recovery. Shutting down the entire economy is not a familiar exercise for policy makers. Therefore, the slow-paced Great Financial Crisis experience likely loomed top of mind and offered reasonableness for further fiscal support to the early recovery already underway from prior stimulus stabilizer packages passed in 2020 including The Coronavirus Aid, Relief and Economic Recovery Act (CARES Act of 2020).

To tailor the appropriate usage of funds, Congress required the Treasury Department to design program parameters for state program approval based on qualified expenses eligible for usage of the funds. The top-level individual or borrower eligibility criteria being that homeowner recipients experienced financial hardship after January 21, 2020. Qualified expenses were more broadly defined by Congress and further detailed by Treasury, creating a menu of categories selectable by participating states to construct their programs. Options included traditional choices for mortgage-related expenses such as reinstating the loan, payment assistance or principal reduction, but also expanded allowances to broader household expenses including homeowners’ utilities, telecom bills, internet payments, hazard insurance costs and other household expenses outside of principal and interest expenses.

The minor challenges confronted early on ranged from operationalizing technology implementations, technical reporting requirements and nuances of timing related to disbursement or reimbursement management across a cascading timeline of newly available state programs. Despite the complexities, these issues were overcome through extensive and continuous coordination among key stakeholders including industry, non-profits, state and federal government and technology suppliers utilized for supporting the roll-out of programs. As of the most recently available program-wide aggregate data from Q3 2023, the Treasury Department estimates that over 450,000 homeowners have been assisted through the program.

Early and Ongoing Successes

The complexity of these large-scale state flow-down programs routinely attract criticisms or one-off cases where temporary lapses in hand-offs, transfers and flawless execution need to be remediated. Taking a step back, the benefits can easily outweigh some of these minor operational hurdles that are bound to arise with 50-plus unique programs with a variety of targeted offerings orchestrated across hundreds of mortgage servicers working with millions of customers. The benefits of the design flexibility of individualized state-specific program elements allow for enriched programs targeting localized issues which may fly under the federal radar.

One such example of design flexibility is the Michigan program, which included the payment of delinquent or unpaid property tax judgments. This program feature is not unique, as other state programs had similar qualified uses, but the results stand out with nearly one-third of funds–$67.1 million–spent went toward property tax payments alone, while another $32 million went toward utilities.

This is not to say a more prescriptive approach with narrower focus does not have advantages of scale, but rather, rigid programs may not always be the appropriate prescription for what is financially ailing households within specific states and counties.

The constraints of COVID-19 and in-person outreach elevated the importance of standardized, complete, accurate and securely transferrable data among participants to efficiently evaluate the most suitable option available to applicants. Leveraging protocols and infrastructure designed under the GFC Hardest Hit Funds program that distributed a similar amount of funds more narrowly across 17 states and the District of Columbia, augmented by stakeholder collaboration and input greatly enhanced the information security, accessibility and overall effectiveness of the HAF program.

For example, mortgage servicer Mr. Cooper emphasized that a common data standard, technology-driven automation, and close partnership with state program representatives resulted in an efficient process for delivering relief to customers needing assistance to remain in their homes. To date, Mr. Cooper has delivered over $520 million in relief across approximately 27,000 customers and continues to work with open programs to support their customers.

State of Programs Today and Going Forward

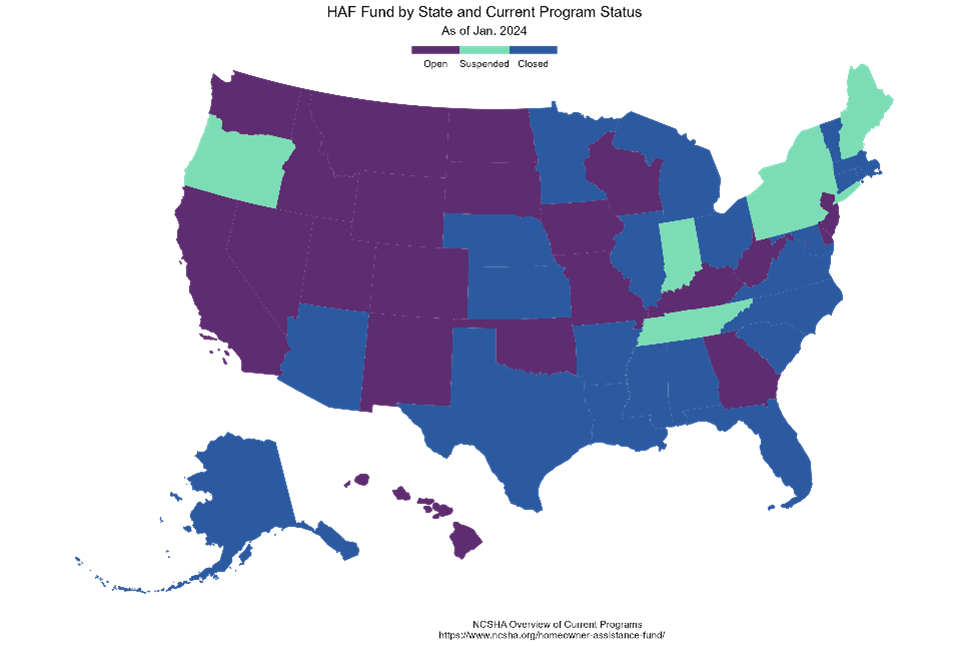

As of January 2024, the National Council of State Housing Agencies reports that 29 states comprising 64% of the original dollars allocated have either closed or suspended new application acceptance for their programs based on limited remaining funds. The states with funds remaining will continue their efforts and the programs will remain another tool available to mortgage servicers in assisting distressed homeowners.

Though demand may be slowing for assistance needs in certain states, large states such as California and New Jersey have funds remaining and both also have seen recent upticks in their unemployment rates which as of December were 5.1% and 4.8% respectively. The dwindling funds in certain states create limitations on the available options for consumers and servicers, but the early rapid deployment to borrowers likely provided more support when demand from borrowers was highest.

Three years since passage of the legislation and effectively almost two years of HAF programs being fully available, HAF has utilized the majority of the funds and appears to be on track to spend nearly all the funds within a four-to-five-year time horizon. Though this may seem like a lengthy amount of time, comparatively the HHF program assistance had just started to hit peak levels of homeowners receiving the benefits in 2013 and 2014 or 3 to 4 years after creation with the final HHF program not formally winding down until 2021.

Meanwhile, recent mortgage performance as measured by 90+ day delinquencies and foreclosure rates has remained steadily near or at historic lows.

Through the Great Financial Crisis and robust response efforts with the roll-out of Making Home Affordable, HHF and HOPE NOW Alliance efforts created a powerful framework for responding to national housing crisis. Key stakeholders in the mortgage industry were well poised with a framework and key lessons learned to drive forward increasingly effective programs in response to COVID. Moving forward, absent the availability of HAF funds and other COVID-19 era programs in the future, the GSEs, state and federal housing agencies have and will likely continue to fine-tune available alternative options in assisting non-pandemic-related hardships.

The HAF program has delivered results to help challenged borrowers since establishment and appears likely to continue to be supportive for homeowners through states where funds remain available. The CARES Act, post-pandemic modifications and loss mitigation are powerful structural changes and having the HAF funds to complement the tools offered through the pandemic have been more streamlined and powerful levers to help at-risk borrowers.