Employment Show Signs of Slowing

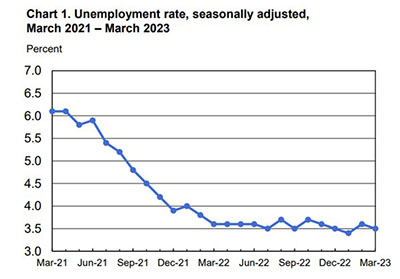

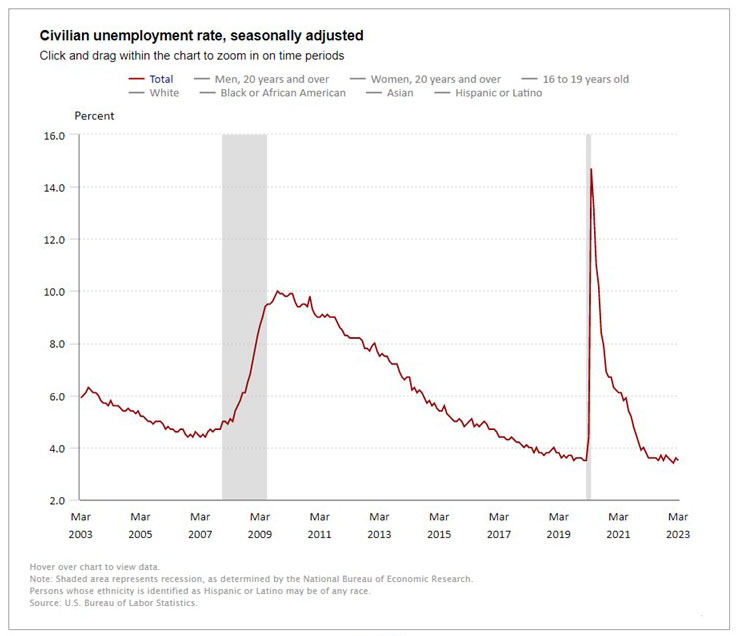

Total nonfarm payroll employment rose by 236,000 in March, the Bureau of Labor Statistics reported Friday—the smallest increase in more than two years, but enough to push the unemployment rate down to 3.5 percent.

Employment continued to trend up in leisure and hospitality, government, professional and business services and health care. The number of unemployed persons, at 5.8 million, changed little. The labor force participation rate, at 62.6 percent, continued to trend up in March. The employment-population ratio edged up over the month to 60.4 percent. These measures remain below their pre-pandemic February 2020 levels (63.3 percent and 61.1 percent, respectively).

BLS revised down total nonfarm payroll employment for January by 32,000, from +504,000 to +472,000, revised up February numbers by15,000, from +311,000 to +326,000, for a net loss of 17,000.

Despite the persistently strong numbers, many economists, including Mike Fratantoni, Chief Economist of the Mortgage Bankers Association, expect the unemployment rate to climb to nearly 5 percent this year.

“Job growth slowed in March, and wage growth decelerated further, with average hourly earnings now up 4.2% over the past 12 months,” Fratantoni said. “These trends and recent data showing fewer job openings and increases in initial claims for unemployment insurance paint a picture of a job market that is still quite strong but beginning to flag, lagging other indicators of a slowing economic activity and tightening credit.”

Fratantoni noted the increase in employment is concentrated in just a few sectors, with the largest gains in leisure and hospitality, where the level of employment remains 2.2% below its pre-pandemic peak. “The question becomes whether consumers will continue to spend on meals out and travel as the economy slows,” he said. “If not, job gains in this sector may also begin to slow.”

Fratantoni added much of the recent job growth has been in lower-paying jobs, which are showing signs of volatility. “MBA expects the unemployment rate will increase to 4.8% by the end of 2023,” he said. “Slowing wage growth should allow inflation in the services to slow over time. MBA expects that the Federal Reserve has reached the peak for this rate cycle, and slowing job growth supports that call, but the most important data points will be those for inflation. If inflation does not show signs of also slowing, the Fed may move ahead with one last rate hike.”

“Job gains in March are strong but slowing, labor supply as measured by overall labor force participation hit a post-Covid high, the unemployment rate moved down and annual wage growth slowed,” said Odeta Kushi, Deputy Chief Economist with First American Financial Corp., Santa Ana, Calif. “The labor market has shown remarkable resiliency and strength in the fact of restrictive monetary policy. Signs of a slowdown have emerged, but a very gradual one.”

Kushi noted while the housing industry, a very interest-rate sensitive sector, has been negatively impacted by the Federal Reserve’s monetary tightening, the construction labor market has not experienced a sharp decline: the jobs openings rate in construction picked up to 4.9%, down from a series high of 5.8% in December 2022, but still strong. The ratio of construction hires per job opening fell in February and remains well below pre-pandemic levels, “indicating it’s more difficult to hire.”

“The continued strength is partially due to the years-long struggle that builders have had attracting and retaining skilled construction workers, making them less likely to part with skilled workers, even in a weaker housing market,” Kushi said. “Additionally, there are a near-record number of homes under construction and you need more hammers at work to build more homes. While the construction labor market has shown resiliency, even in the face of a slowing housing market, it is slowing.”

“The labor market is moving back toward balance, not just through weaker labor demand, as has been evident in earlier reports on job openings and layoffs, but also through improving labor supply,” said Sarah House, Senior Economist with Wells Fargo Economics, Charlotte, N.C. “On balance, this is the type of employment report we believe policymakers at the FOMC want to see: job growth slowing in an orderly fashion, labor supply expanding and wage growth that is edging closer to rates that are consistent with the central bank’s 2% inflation target. The inflation fight remains far from finished, but through the month-to-month noise there are leading indicators to suggest progress is being made. We remain of the view the FOMC will hike the fed funds rate by 25 bps at its May 3 meeting, but it could be the last rate hike of the cycle as policymakers keep rates on hold for an extended period of time and let the medicine take.”

The report said average hourly earnings for all employees on private nonfarm payrolls rose by 9 cents, or 0.3 percent, to $33.18. Over the past 12 months, average hourly earnings have increased by 4.2 percent. Average hourly earnings of private-sector production and nonsupervisory employees rose by 9 cents, or 0.3 percent, to $28.50.

The average workweek for all employees on private nonfarm payrolls edged down by 0.1 hour to 34.4 hours in March. In manufacturing, the average workweek was unchanged at 40.3 hours, and overtime remained at 3.0 hours. The average workweek for production and nonsupervisory employees on private nonfarm payrolls was unchanged at 33.9 hours.