4Q GDP Shows Subtle Signs of Slowing

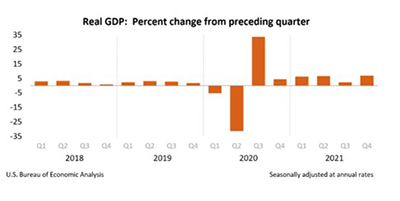

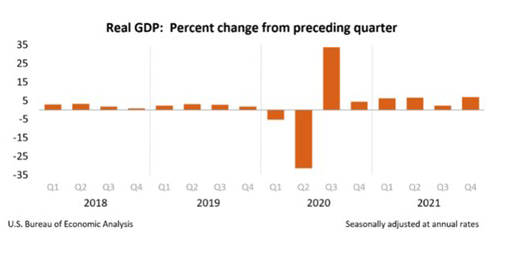

Despite the potential impact of Omicron variant on the U.S. economy, fourth quarter gross domestic product clipped along at nearly 7 percent, the Bureau of Economic Analysis reported Thursday. But the numbers might not be all that they seem, analysts said.

For 2021, BEA said real GDP increased by 5.7 percent.

BEA said real GDP increased at an annual rate of 6.9 percent in the fourth quarter, according to its “advance” estimate, which is based on incomplete source data subject to further revision in February and March. The increase in real GDP primarily reflected increases in private inventory investment, exports, personal consumption expenditures and nonresidential fixed investment that were partly offset by decreases in both federal and state and local government spending. Imports, which are a subtraction in the calculation of GDP, increased.

In the third quarter, real GDP increased 2.3 percent.

“Two items of note stick out in this preliminary read on economic growth in the fourth quarter of 2021: supply-chain issues challenged many sectors of the economy, and inflation is running well above the Federal Reserve’s target,” said Mike Fratantoni, Chief Economist with the Mortgage Bankers Association. “While household spending growth, particularly on services, was steady, most of the pickup in GDP growth was due to a significant jump in business spending on inventories. This likely reflects the ongoing challenges so many sectors of the economy have had with supply-chain constraints.”

Fratantoni said some companies may move to higher steady state inventory levels going forward to prevent the disruption that supply-chain issues have caused, “and this ongoing restocking behavior could continue to lead to above trend growth in 2022.”

Tim Quinlan, Senior Economist with Wells Fargo Securities, Charlotte, N.C., said the headline number could have been higher, but instead signals a slowing in the economy.

“While to some extent the year-end surge was a function of steady consumer and business spending, both petered out at the end of the year as Omicron cases climbed and hospitalizations followed,” Quinlan said. “Not knowing what was coming in terms of the pandemic, many retailers stocked up in anticipation of strong holiday sales and businesses continued to pull out all the stops to source much needed inventories. But after a strong October and decent November, retail sales ended the year with a flop in December.”

Meanwhile, Quinlan noted, the challenge businesses have already faced finding workers was exacerbated by increased absenteeism due to illness related to the new variant. Against that backdrop, inventories started stacking up. The result of this stockpiling was a 4.9 percentage point boost to headline growth from inventories.

“We had anticipated a build, but this was even larger than we had penciled in,” Quinlan said. “That makes it difficult for inventories to provide a lift in the first quarter. In the absence of that boost, our already modest expectation for 2.8% GDP growth in Q1 may get revised even lower.”

Quinlan said the well-above trend rate of growth can be linked to the massive stimulus that was poured into the economy—from direct stimulus checks to consumers, to supplements to jobless benefits and expansions of the Child Tax Credit. “Transfer payments over the past couple of years have allowed consumers to have their cake and eat it too,” he said. “In the absence of that stimulus, consumer spending is poised to slow.”

The report said core PCE came in at almost 5% in the fourth quarter. “This data point without a doubt puts an exclamation point on the Fed’s statement yesterday that inflation remains well above their target,” Fratantoni said.

The report said the increase in private inventory investment was led by retail and wholesale trade industries. Within retail, inventory investment by motor vehicle dealers was the leading contributor. The increase in exports reflected increases in both goods and services. The increase in exports of goods was widespread, and the leading contributors were consumer goods, industrial supplies and materials, and foods, feeds, and beverages. The increase in exports of services was led by travel. The increase in PCE primarily reflected an increase in services, led by health care, recreation, and transportation. The increase in nonresidential fixed investment primarily reflected an increase in intellectual property products that was partly offset by a decrease in structures.

The decrease in federal government spending primarily reflected a decrease in defense spending on intermediate goods and services. The decrease in state and local government spending reflected decreases in consumption expenditures (led by compensation of state and local government employees, notably education) and in gross investment (led by new educational structures). The increase in imports primarily reflected an increase in goods (led by non-food and non-automotive consumer goods, as well as capital goods).

Real GDP accelerated in the fourth quarter, increasing 6.9 percent after increasing 2.3 percent in the third quarter. The acceleration in real GDP in the fourth quarter primarily reflected an upturn in exports, accelerations in private inventory investment and PCE, and smaller decreases in residential fixed investment and federal government spending that were partly offset by a downturn in state and local government spending. Imports accelerated.

For 2021, real GDP increased 5.7 percent, compared to a decrease of 3.4 percent in 2020 (table 1). This reflected increases in all major subcomponents, led by PCE, nonresidential fixed investment, exports, residential fixed investment and private inventory investment. Imports increased.