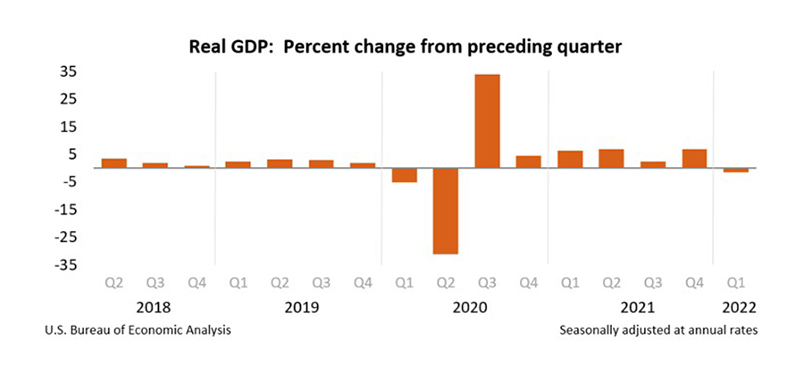

1st Quarter GDP Falls 1.4%

U.S. gross domestic product fell for the first time in two years, the Bureau of Economic Analysis reported Thursday, although analysts did not seem overly concerned.

BEA reported real GDP decreased at an annual rate of 1.4 percent in the first quarter, according to the first (advance) of three monthly estimates, based on source data that are incomplete or subject to further revision.

In the fourth quarter, real GDP increased by 6.9 percent.

BEA attributed the decrease in real GDP to decreases in private inventory investment, exports, federal government spending and state and local government spending, while imports, which are a subtraction in the calculation of GDP, increased. Personal consumption expenditures, nonresidential fixed investment and residential fixed investment increased.

The decrease in private inventory investment was led by decreases in wholesale trade (mainly motor vehicles) and retail trade (notably, “other” retailers and motor vehicle dealers). Within exports, widespread decreases in nondurable goods were partly offset by an increase in “other” business services (mainly financial services). The decrease in federal government spending primarily reflected a decrease in defense spending on intermediate goods and services. The increase in imports was led by increases in durable goods (notably, nonfood and nonautomotive consumer goods).

The increase in PCE reflected an increase in services (led by health care), partly offset by a decrease in goods. Within goods, a decrease in nondurable goods (led by gasoline and other energy goods) was partly offset by an increase in durable goods (led by motor vehicles and parts). The increase in nonresidential fixed investment reflected increases in equipment and intellectual property products.

Current‑dollar GDP increased 6.5 percent at an annual rate, or $379.9 billion, in the first quarter to a level of $24.38 trillion. In the fourth quarter, GDP increased 14.5 percent, or $800.5 billion (table 1 and table 3).

The price index for gross domestic purchases increased 7.8 percent in the first quarter, compared with an increase of 7.0 percent in the fourth quarter (table 4). The PCE price index increased 7.0 percent, compared with an increase of 6.4 percent. Excluding food and energy prices, the PCE price index increased 5.2 percent, compared with an increase of 5.0 percent.

“The U.S. economy shrank for the first time since the first half of 2020,” said Joel Kan, Associate Vice President of Economic and Industry Forecasting with the Mortgage Bankers Association. “The good news is that consumer spending remained strong, particularly for services, as much of that sector has returned close to pre-pandemic levels. Households continue to benefit from a strong job market and wage growth.”

Kan noted spending on non-durable goods fell for the first time in more than a year, potentially impacted by rapidly increasing prices. “Business investment had its largest contribution to overall growth in a year, indicating additional underlying strength in the economy,” he said. “We expect the Fed to proceed with its plans to further tighten monetary policy over the course of 2022 as inflation has not shown signs of slowing yet, especially given the resilience in consumer spending.”

“Net exports robbed the GDP bank in the first quarter, slicing 3.2 percentage points off of the headline growth rate, inventories and government spending cuts took another 0.8 points and 0.5 points, respectively,” said Tim Quinlan, Senior Economist with Wells Fargo Economics, Charlotte, N.C. “Those effects swamped what was actually a decent quarter for business and consumer spending and put the headline number underwater with a contraction of 1.4%.”

Quinlan said whether by design or circumstance, “GDP math has some built-in features that in practice serve as counterweights to volatility. For example, a strong quarter for consumer and business spending is often associated with slower growth or outright declines in inventories and perhaps a drag from trade if imports outpace exports that quarter as well.”

Quinlan added to the extent that higher prices force tough decisions for households, “our bet is that continued service spending will be sustained even if it has to come at the cost of slower growth or outright declines for durables. That implies that this era of a wildly expanding trade deficit will transition to one of modest narrowing. In short, the drag from trade will begin to dissipate and perhaps even become a positive for GDP growth if the trade gap narrows.”